Highlights

- Higher than expected inflation and fears of recession rattled stock and bond markets.

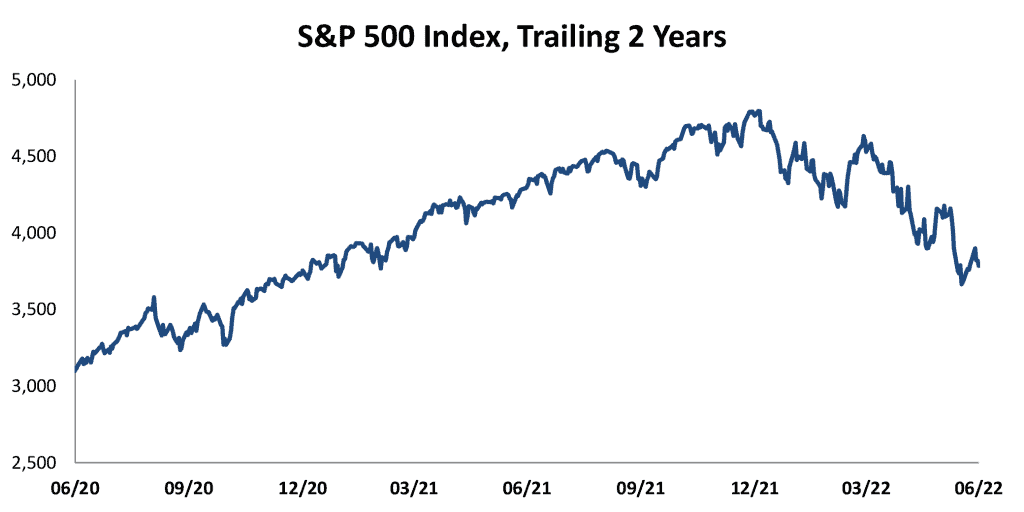

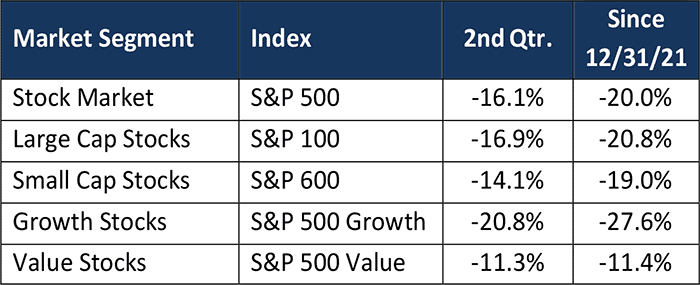

- The S&P 500 returned -16.1% in the second quarter, bringing its 2022 loss to 20.0%.

- All equity sectors had losses in the second quarter, with Energy the only one positive in 2022.

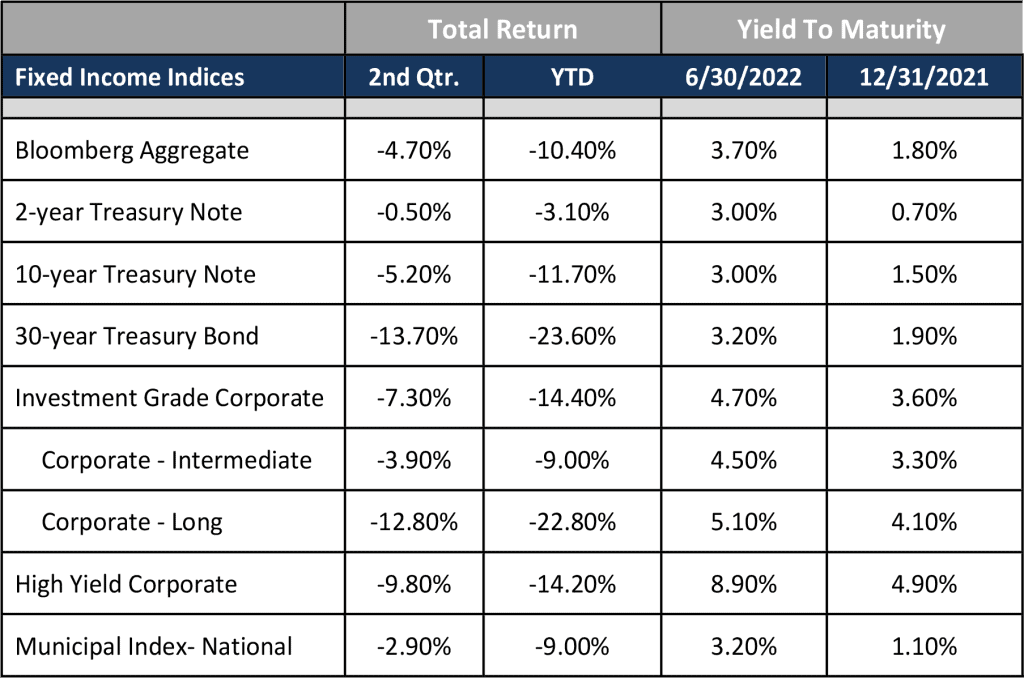

- The Bloomberg Aggregate bond index returned -4.9% for the quarter and -10.4% year-to-date.

- Value stocks outperformed growth stocks by 9.5% in the quarter and 16.2% year-to-date.

- The rate of inflation continued to increase, with year-over-year CPI up 8.6% in May.

- The Federal Reserve appears willing to risk a recession in order to reduce inflation.

Equities

Higher energy costs that affected a broad range of products and services, along with continued supply chain problems stemming from China’s COVID lockdown policy, produced a higher rate of inflation in the second quarter. In response, the Fed moved more aggressively to raise short-term rates at its mid-June meeting. This higher inflation, the Fed’s response, and growing fears of a recession resulted in substantial losses in the equity markets. The S&P 500 returned -16.1% in the second quarter, which brought its total return for the first six months of the year to -20.0%.

Large cap stocks lost 16.9% in the second quarter, resulting in a 20.8% loss for the first half of the year. Small cap stocks did slightly better, outperforming large caps by 2.8% in the second quarter and by 1.8% year-to-date. Value stocks, which had been relatively unscathed in the first quarter, lost 11.3% in the second quarter as fears of recession impacted a broader range of companies than the primarily high-multiple companies hurt by rising rates in the first quarter. However, value stocks lost only a little more than half of what growth stocks lost in the second quarter, outperforming growth stocks by 9.5% in the quarter and by 16.2% year-to-date.

The three best performing sectors in the second quarter were Consumer Staples, Utilities, and Energy, which were all down about 5%. The same three sectors were also the best performers in the first half of the year. Although oil prices increased slightly in the second quarter, the Energy sector posted a negative return for the quarter as investors focused on the possibility of a recession. Nevertheless, Energy was the only sector to post a positive return year-to-date (+31.9%). The worst performing sectors for both the quarter and the first six months of 2022 were Consumer Discretionary, Communication Services, and Information Technology. These sectors lost over 23% on average in the quarter and 30% year-to-date.

With the fading of the fiscal stimulus effects, analysts expect earnings for companies in the S&P 500 to increase 6% in 2022. However, with corporate profit margins at record highs and the effects of higher inflation on consumer spending and corporate costs just beginning to be seen, it seems likely that corporate earnings will be weaker than the current consensus expectations. The forward 12-month P/E ratio for the S&P 500 (reported earnings) stood at 16.9 on June 30, down from 22.7 at the end of the year. With the strong sell-off in the high multiple stocks, the weight of the biggest 10 stocks in the S&P 500 has decreased to 28.1% from 30.5% at the end of the year, with the P/E ratio on the next 12 months’ earnings for those stocks falling from 33.2 to 23.6 in the last six months. Meanwhile, the forward P/E ratio of the remaining 490 stocks in the S&P 500 has dropped from 19.7 to 15.9.

Fixed Income

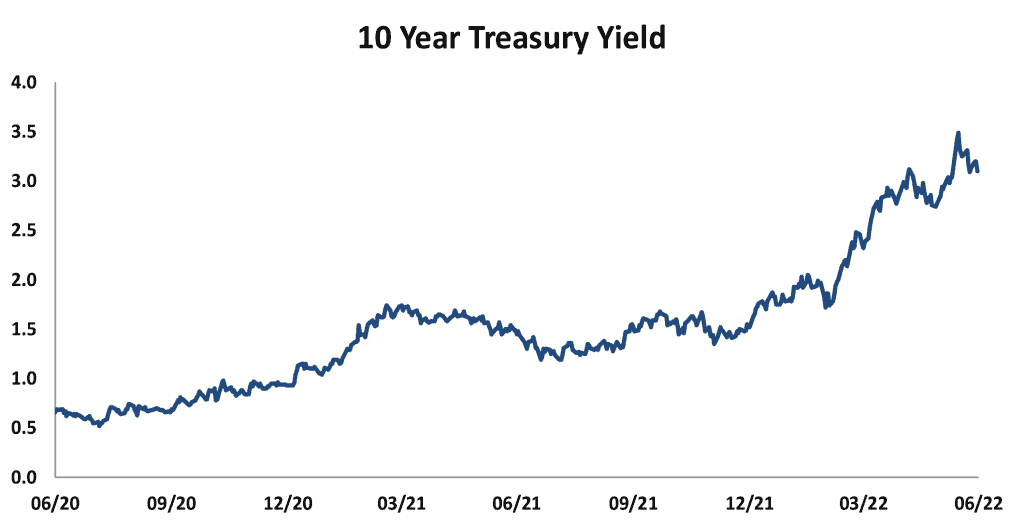

The June 10 Consumer Price Index report surprised investors with the strength of inflation it showed. Prices in May rose 1% over the prior month and 8.6% over the prior year. While food and energy prices were up 10% and 35%, respectively over the last year, all other prices rose 6%. This level of inflation led the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to increase the Fed Funds target rate range by 0.75% to 1.5% – 1.75% at its meeting on June 15. Chairman Powell also suggested that another 50-75 basis point increase was likely in July. In addition, the FOMC reiterated its intention to reduce its holdings of Treasury securities by $30 billion a month (increasing to $60 billion in September) and its holdings of mortgage securities by $17.5 billion a month (increasing to $35 billion in September).

Bonds provided relatively more protection to investors in the second quarter than they did in the first quarter, although the persistence of higher-than-expected inflation led to additional losses in fixed income portfolios. While the S&P 500 lost over 16% in the second quarter, the Bloomberg Barclay’s Aggregate, the broadest measure of the investment-grade fixed income market, lost only 4.7%, an improvement over its 5.9% loss in the first quarter. Treasury yields increased across the yield curve, which continued to flatten as the largest increases occurred on the very short end. For example, the 3-month Treasury bill yield increased by 1.2% to 1.7% while the 10-Year Note increased by 0.7% to 3.0%. As shown in the table below, longer term bonds fared substantially worse than shorter-term issues, both in the second quarter and the first half of the year, with comparable maturity corporate securities producing worse results than Treasuries due to the increase in risk premiums (credit spreads). The widening of credit spreads was particularly pronounced in lower quality issues. However, municipal bonds produced better returns than Treasuries or corporates for both the quarter and year-to-date periods.

Market Environment

The market’s decline this year has been driven almost entirely by valuation multiple contraction. But there are numerous signs that the risk of a recession is increasing as consumers try to maintain spending levels in the face of higher prices. Over the last few months, savings rates have fallen and credit card balances have increased. Consumers are also reducing purchases of more discretionary items in order to maintain spending on more essential ones. Any decline in demand due to higher prices, coupled with the cost pressures of higher energy prices and supply-chain related cost increases, would lead to lower corporate earnings and lower stock prices.

At this point, the Federal Reserve seems committed to bringing the rate of inflation back into line with its 2.0% target, even at the risk of causing a recession. However, the Fed can’t produce more energy, fix supply chain problems, or stem a de-globalization that seems likely to reduce productivity and increase costs in the future. The only thing it can do is increase the cost of money by increasing short-term rates and letting long-term rates rise (Quantitative Tightening). Many economists believe that the Fed can tighten policy and avoid a recession due to the average household’s level of savings. However, history suggests that that the Fed is likely to maintain its restrictive policy longer than necessary, just as it did with its accommodative policy in 2021.

In addition to increasing the chance of a recession, the Fed’s more restrictive monetary policy creates other risks to economic health. For example, the rise in U.S. yields has contributed to a very rapid appreciation in the value of the U.S. Dollar relative to other currencies. This appreciation makes it more expensive for foreign borrowers to service dollar-denominated debt. It also reduces the dollar value of foreign earnings for U.S. multinational companies. A stronger dollar also serves to increase inflation in countries that import goods priced in dollars (e.g., oil) with secondary consequences. In the case of Europe, as the European Central Bank raises rates to fight inflation, it creates significant problems for the heavily indebted, economically weaker southern European countries such as Italy and Greece, thereby threatening their ability or willingness to remain part of the Eurozone.

Will the Federal Reserve actually do “whatever it takes” to bring inflation back to its target? In 2019, the Fed reversed its monetary tightening policy on the basis of a decline in the stock market and potential weakness in the economy. While the central bank insists that it will be resolute in letting rates rise enough to dampen demand, there are structural constraints to how high rates can go. Thanks to the unprecedented spending by the U.S. government during the pandemic, outstanding debt grew by 31% ($6.7 trillion) over the last two years to $30.4 trillion. The Fed purchased $3 trillion of that new debt and the markets absorbed $3.7 trillion. Approximately $6.1 trillion matures within the next year and will have to be refinanced at higher rates. As the Federal government continues to run deficits to the tune of $1 trillion a year and the Fed allows up to $3 trillion of the debt it purchased to be refinanced in the open market, buyers will likely require higher interest rates. At some point, the interest burden becomes unsustainable, and the Fed can’t afford, politically or economically, to continue to let rates rise.

Focusing on Long-Term Results

These remain challenging times for all investors. Navigating the risks in this market environment requires consistent focus on long-term goals and an appropriate allocation of assets. At Buckhead Capital, we work hard to help our clients clarify and achieve their financial goals. We try to understand the lessons that markets have provided and to use that knowledge in structuring portfolios to preserve and grow our clients’ capital. We continue to emphasize achieving an appropriate return for the risk taken. We do this not only through asset allocation (the mix of stocks, bonds, and cash) but also through individual security selection, sector weightings, and, in fixed income, target portfolio maturities/durations. This attention to risk management has historically produced better risk-adjusted returns over full market cycles. We continue to believe that this market cycle will be no exception.